Despite increasing awareness of the impact of eating red meat, there seems little appetite at present for government intervention to support people to eat less. This is the finding of our new research published in the Journal of Environmental Psychology, and is in contrast to policies targeting healthy diets.

Fewer than half of a sample of the UK public expressed support for any of six policies to reduce meat consumption in the study, conducted with colleagues from the University of Cambridge and Aston University. Banning advertising and increasing the price of meat were the least supported while running a media campaign or adding ecolabels received greater backing.

Similar policies aimed at reducing the consumption of alcohol, tobacco and snack foods were supported by the majority of participants in previous research, suggesting that targeting meat is a particularly sensitive issue.

But the backdrop to this is the 20% reduction in meat and dairy consumption needed by 2030 for the government to achieve its net zero target on carbon emissions. The National Food Strategy recommends a 30% reduction by the same date and others suggest reductions of up to 85% are required.

What did we do?

In an online experiment, we asked 2,215 UK adults to rate the acceptability of six policies aimed at reducing the consumption of red and processed meat. The policies were: adding ecolabels to outline climate impacts to foods; running a media campaign; limiting the proportion of meat-based options at public sector organisations to 25%; providing government grants to beef producers to switch to crops; increasing price; and banning advertising.

Before rating the policies, participants were randomised to see one of two statements, framing policy outcomes either as benefiting health or benefiting the environment.

What did we find?

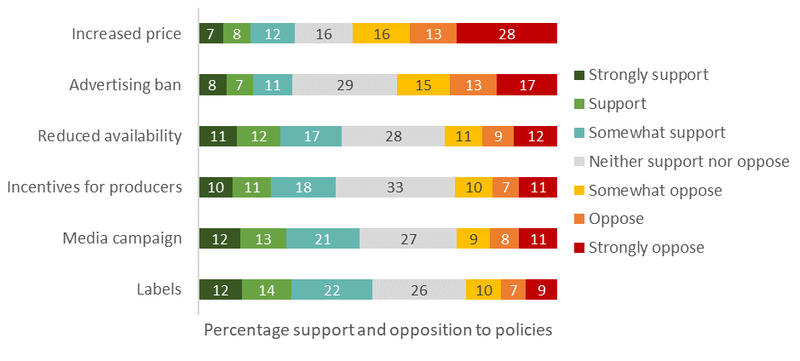

- The most supported policies were adding labels, running a media campaign, limiting the proportion of meat-based options at hospitals and other public sector organisations to 25%, and providing government grants to beef producers to switch to crops. But none were supported by a majority of participants: these had between 38%-48% support.

- Only around a quarter of participants supported increasing prices via a 20% tax or banning advertising.

- Between a quarter and a third of participants were undecided on each policy, with the notable exception of targeting price, where only 16% did not express a view.

- We found no evidence for a difference in acceptability if we suggested these policies would lead to benefits for health compared to suggesting these would lead to benefits for the environment.

What can we take from this?

If trends towards eating less meat continue, the acceptability of policy action may increase, though the rate of change is currently too slow to meet policy goals. Although more people seem to support the idea of eating less red meat, there seems little appetite for government intervention to achieve this. This contrasts with what we know about policies targeting healthy diets.

We take some hope that given the large proportion of people who were undecided, opinions may still be being formed with regard to these policies. Making the case for action could help boost support.